What prevent us from learning new programming skills

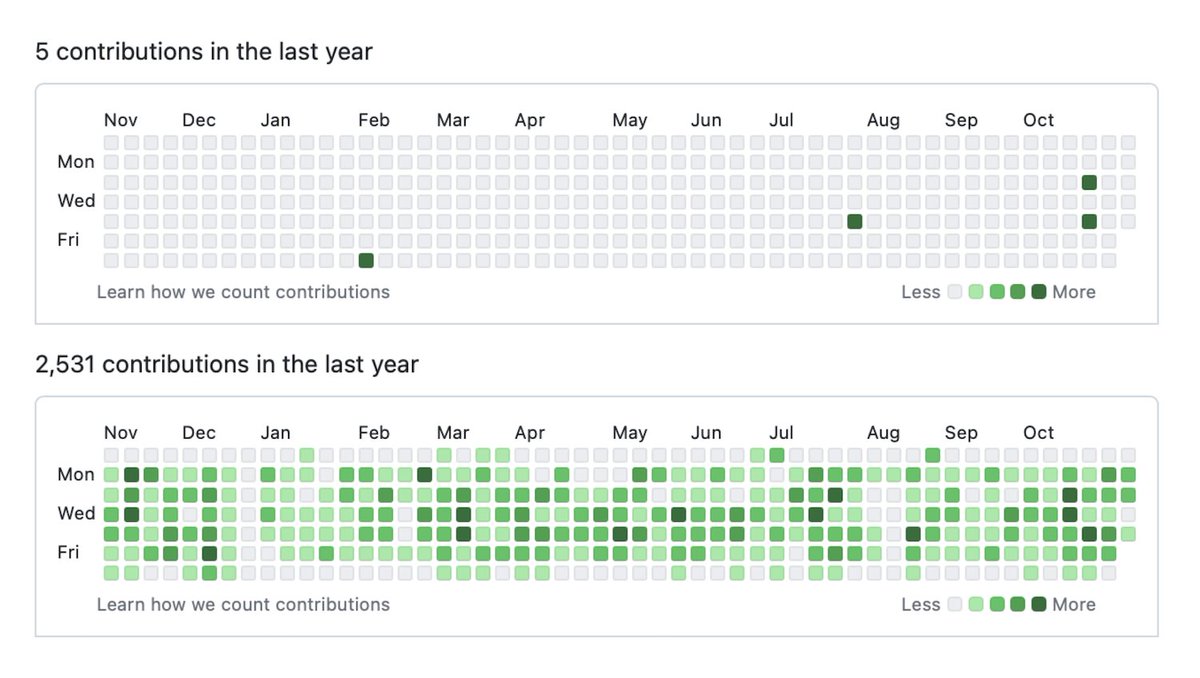

A couple of days ago, I ran into a Twitter post: https://x.com/VincentS/status/1722674693616910450?s=20

Although I recently turned to Bluesky for social networking (https://bsky.app/profile/changliao.bsky.social),

If you can open the Twitter post with the figure, you might wonder what the intention of this post is. There are a few comments on this post as well. There are some quick takeaways based on my understanding. First, some developers don’t actually write code but might provide suggestions to other developers. Some developers take the time to actually write the code. One comment also pointed out that some GitHub activities are also fake because they are not actually programming activities but instead spell checks. This reminds me that some people also buy GitHub stars for some purposes.

I am from an academic background, so this reflects some reality. Most senior modeling researchers do not code or don’t even have a GitHub account, yet they still claim they are modelers. In contrast, a PhD/postdoc or early career scientist may still participate in programming activities. Thus, their GitHub profile may resemble the figure’s lower part.

So, what prevents senior modelers from coding? My experience and observation provide me with several explanations:

- Senior modelers don’t have time for programming. Some are busy with proposals and team building and often have to lend heavy lifting to early careers. Especially if you consider the technology of GitHub is relatively new, many modelers came to fame before GitHub was born.

- Senior modelers actually need to gain coding skills. This is also possible because many modelers are more mathematical-based or equation-based and need more experience in computer programming. I have also seen peers use Excel for modeling, which differs from the standard practice.

- Senior modelers stopped learning new skills. This might be a deeper problem that most of us ignore.

I will skip reasons 1 and 2 because reason 3 feels more personal. My personal experience is that I received most of my programming training during my undergraduate years, from 2005 to 2009. Most of my C/C++ knowledge was taught in classes. I also had some courses taught in MATLAB for image processing for remote sensing datasets. I self-taught IDL (to replace MATLAB) and C# during my master’s program between 2009 and 2012. I then re-picked up C++ during my PhD 2012-2017. After my Ph.D., I self-taught Python to replace IDL.

I have used Python and C++ daily, but I still feel I need to improve my programming skills. Why? Because I still need to catch up with the latest C++ and Python features. For an Earth scientist, once you find a solution to do a task, you are very often likely to stick with that solution for a long time. This is what we call a habit. I have seen peers use MATLAB and NCL and refuse to switch to Python even though they know NCL will not be supported.

As scientists, we must focus on the science, not the process or the solution.

On the other hand, our advances in high-performance computing (HPC) often shield our limits in programming skills. I have also seen peers write inferior performance code and run it on HPC. No one will question the code if running on HPC takes a short time. If a code takes a lot of time to run on HPC, most modelers will consider this a computationally expensive code. Most of us will not question whether it is because the code was poorly written. That is also why we need FAIR, so peers can help each other to improve the code.

Most organizations need a mechanism to train scientists to become better modelers. And it ultimately depends on personal career development. Since academia often only rewards publications, only some scientists will invest time in programming. To stay in the game, they will instead use more expensive computers (more considerable project funding) or hire early careers to compensate for the computational demands. Once an early career becomes senior and accesses more resources, they will do the same.